View Jesse’s full photo set at flickr.com

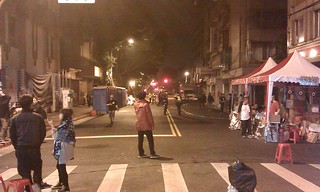

The sun sets on several thousand gathered in Taipei. Police stand guard with riot shields and batons blocking roads and entrances. Streets overflow with students—some standing, most sitting on cardboard, Mylar heat blankets, or interlocking foam pads. Tents and booths line walkways. Traditional Taiwanese food vendors sit at the outskirts. Projection screens and stages can be found at the corner of every block, each with a different guest speaker. Sweepers patrol, armed with brooms and dustpans. The scene is clean. No one litters. Everyone is a volunteer but the police. Sunflowers and yellow banners are everywhere.

The sun sets on several thousand gathered in Taipei. Police stand guard with riot shields and batons blocking roads and entrances. Streets overflow with students—some standing, most sitting on cardboard, Mylar heat blankets, or interlocking foam pads. Tents and booths line walkways. Traditional Taiwanese food vendors sit at the outskirts. Projection screens and stages can be found at the corner of every block, each with a different guest speaker. Sweepers patrol, armed with brooms and dustpans. The scene is clean. No one litters. Everyone is a volunteer but the police. Sunflowers and yellow banners are everywhere.

This is a movement unlike anything I’ve seen. Anyone who has personally encountered a head of Sate understands the term “electricity”. If you’re standing outside the White House, for instance, not even paying attention, you may suddenly feel an enormous “jolt” of emotional energy, even with no noise or activity. Then, you unconsciously turn to look at the White House lawn and, as it just so happens, the President emerged not two seconds ago and is making his way to the helicopter. This feeling of sudden energy is “political electricity”. It doesn’t occur all the time, but it can be experienced on a smaller scale with pastors, preachers, corporate CEO’s, and often police. It tends to be stronger with leaders who have more responsibility.

This is a movement unlike anything I’ve seen. Anyone who has personally encountered a head of Sate understands the term “electricity”. If you’re standing outside the White House, for instance, not even paying attention, you may suddenly feel an enormous “jolt” of emotional energy, even with no noise or activity. Then, you unconsciously turn to look at the White House lawn and, as it just so happens, the President emerged not two seconds ago and is making his way to the helicopter. This feeling of sudden energy is “political electricity”. It doesn’t occur all the time, but it can be experienced on a smaller scale with pastors, preachers, corporate CEO’s, and often police. It tends to be stronger with leaders who have more responsibility.

Events of the last two weeks in Taipei are extraordinary for this reason—nearly all of the students in and around the legislative chamber have “political electricity”, while the police, mafia, and politicians have none. One can’t learn this from watching TV. You have to be on the ground in order to see it.

Events of the last two weeks in Taipei are extraordinary for this reason—nearly all of the students in and around the legislative chamber have “political electricity”, while the police, mafia, and politicians have none. One can’t learn this from watching TV. You have to be on the ground in order to see it.

In many ways, the organization structure of the Sunflower movement resembles any young and thriving organization, such as Apple or the International House of Prayer in Kansas City. Leaders have “electricity”. Mistakes, complaints, and wanna-be leaders are everywhere, but the effort seems to have “luck” and emerges from every manure pile smelling like a bouquet of roses. This movement bears all the beauty and flaws of every great wave of history—the kind that can’t be contrived.

The standoff between students and police has multiple layers, like an onion. Inside the Legislative Yuan’s chamber, students, led by Lin Fei-fan (林飛帆) and Chen Wei-ting (陳為廷) control the floor and the roof. A small “inner perimeter” of police guard the front and side entrances of the Legislative Yuan, mainly preventing riots, keeping the peace, and limiting access to doctors, lawyers, professors, agents of the press, and student leaders. Beyond this small inner police perimeter is another perimeter of students and peaceful demonstrators occupying the Legislative Yuan’s front and side parking lots. A second perimeter of police, beyond the parking lot occupants, control a few inner courtyards and back allies. The surrounding streets contain the third and largest group of peaceful demonstrators, numbering in the thousands. Beyond those streets is a third and larger perimeter of police, mainly controlling intersections and crosswalks at outlying roads.

The standoff between students and police has multiple layers, like an onion. Inside the Legislative Yuan’s chamber, students, led by Lin Fei-fan (林飛帆) and Chen Wei-ting (陳為廷) control the floor and the roof. A small “inner perimeter” of police guard the front and side entrances of the Legislative Yuan, mainly preventing riots, keeping the peace, and limiting access to doctors, lawyers, professors, agents of the press, and student leaders. Beyond this small inner police perimeter is another perimeter of students and peaceful demonstrators occupying the Legislative Yuan’s front and side parking lots. A second perimeter of police, beyond the parking lot occupants, control a few inner courtyards and back allies. The surrounding streets contain the third and largest group of peaceful demonstrators, numbering in the thousands. Beyond those streets is a third and larger perimeter of police, mainly controlling intersections and crosswalks at outlying roads.

The Sunflower night watch is volunteer posse led by John Alias*. The posse’s members consist of an array of conscientious street gang volunteers, Kung Fu and EMC trained fighters, and a growing group of skaters. Armed with little more than gloves, this band of rough and tough, street smart “youngin’s” has shut down several nighttime attempts from the mafia to incite violence. They have a kind of warfare “favor” scarcely seen since Joshua marched at Jericho.

The Sunflower night watch is volunteer posse led by John Alias*. The posse’s members consist of an array of conscientious street gang volunteers, Kung Fu and EMC trained fighters, and a growing group of skaters. Armed with little more than gloves, this band of rough and tough, street smart “youngin’s” has shut down several nighttime attempts from the mafia to incite violence. They have a kind of warfare “favor” scarcely seen since Joshua marched at Jericho.

In one instance, Chang An-le (張安樂), the “White Wolf” leader, as he is also known, showed up with a mob of 500, likely on his payroll. The Taipei police did not take the opportunity to make arrests, though many in Chang’s mob were notorious criminals. Moreover, the mob was allegedly in violation of a local “parade” ordinance. “We’re just passing by,” the mob claimed. The police shrugged and did nothing. The evermore apparent cooperation between some leaders of the police and the mafia is grotesque. But after yelling and shouting at the peaceful protesters for about an hour, the mafia’s “White Wolf’s 500″ left without incident. Peace resumed. John’s watch continued.

At dusk, public speakers give way to celebrity musicians. After the nightly musical protest performances, screens show thought-provoking and historical documentaries. At midnight the videos stop, screens go blue, and demonstrators take to their sleeping bags and tents.

9:00 pm—A woman stands near John’s base to ostensibly complain on behalf of the local community. “We get about two complaints each day like this,” John explains. “But most of our reports from local residents are positive and supportive of the Sunflower movement. The mafia-controlled media never reports that part.”

1:00 am—A posse leader storms into John’s base and demands an emergency meeting: too many chiefs and not enough Indians. John solves the entire conflict with the wisdom and eloquence of a grandfather. After 10 minutes of mediation, everyone is joking and laughing over a cigarette.

1:15 am—A call squawks over the radio…

1:15 am—A call squawks over the radio…

Radio: Suspicious person sighted.

John: Can you describe him?

Radio: He is indescribable.

…Everyone in the base laughs. John heads out into the night with his posse to track the reported suspect. The ally is dark and eerie—the kind of place a mother tells her children never to go at night. A black Mercedes pulls up on one of the side streets. Five mafia gangsters step out of the vehicle with clubs as John arrives on the scene. Realizing the situation, the five thugs jump back into the car. Tires squeal. The Benz drives off. Peace continues for one more night. John continues his patrol and returns to base an hour later.

2:00 am—Mist rain begins to fall. Demonstrators awaken in the parking lot outside of the Legislative Yuan and relocate to the roofed walkway for the remainder of the night. Demonstrators in the street are already in their tents. All goes quiet.

2:00 am—Mist rain begins to fall. Demonstrators awaken in the parking lot outside of the Legislative Yuan and relocate to the roofed walkway for the remainder of the night. Demonstrators in the street are already in their tents. All goes quiet.

6:00 am—A drunken man wearing a suit with no tie appears at the side entrance, the only access point, and begins to proclaim his opposition to the students. Like any drunk, he quickly changes his song, “What the h*ll… F*ck the government! This is great what you’re all doing.”

After a few hours of entertainment and laughs from both students and police, the man sobers slightly and returns to his former message—that the students are wrong, that Taiwan’s President should be trusted, and that no one should occupy government buildings regardless of whether the government ignores their own Constitution. Bored, the students begin to ignore the unshaven drunkard.

Finally, one angry lady steps in to argue with the drunk man. Voices raise, arms flailing.

As the only American on the scene, I instantly stepped into the circle, along with three student leaders in order to prevent an incident. Everyone else remained calm. Three minutes later, two new police arrived and escorted the drunken trouble maker away from the scene. Peace returned and the sun continued to rise.

8:30 am—A box of small coffees from McDonald’s was donated by a local sympathizer of the movement. A young man walks past with a “President Ma” doll. “He is garbage, made from garbage,” the student says as he makes his one-minute pose for the camera.

8:30 am—A box of small coffees from McDonald’s was donated by a local sympathizer of the movement. A young man walks past with a “President Ma” doll. “He is garbage, made from garbage,” the student says as he makes his one-minute pose for the camera.

9:00 am—I head to McDonald’s for breakfast with a friend as the “White Wolf” mafia leader himself, Chang An-le (張安樂), dashes past us on the empty sidewalk, wearing his usual round spectacles, carrying a small camera and a big frown.

He’s easy to identify since there are so many pictures of him posing with the Taiwanese police and he’s the only man in Taipei who casually dresses in “mom jeans” like a retired Hong Kong businessman. Though he was easy to recognize, Chang lacked the “political electricity” held by Hong Kong mobsters and Chicago politicians. To me, he came across as a deposed prince, even before my breakfast companion pointed him out. A sunflower sat in a plastic bottle on the quiet street. Most of the people slept in tents.

10:00 am—Lin Fei-fan (林飛帆), known for his clean cut hair, signature round glasses, and olive drab cotton jacket, emerges from the legislature to make his morning appearance. He is instantly mobbed by reporters and camera crews. The issue of the day is an alleged outcry from local residents. The complaints are trumpeted by a man who doesn’t even live in the community—raising questions about whether the complaints are genuine. After stopping at three different places in the parking lot, being mobbed by the press at each point, Lin returns to the occupied chamber, his daily “good morning” rounds having been a success.

10:00 am—Lin Fei-fan (林飛帆), known for his clean cut hair, signature round glasses, and olive drab cotton jacket, emerges from the legislature to make his morning appearance. He is instantly mobbed by reporters and camera crews. The issue of the day is an alleged outcry from local residents. The complaints are trumpeted by a man who doesn’t even live in the community—raising questions about whether the complaints are genuine. After stopping at three different places in the parking lot, being mobbed by the press at each point, Lin returns to the occupied chamber, his daily “good morning” rounds having been a success.

11:00 am—Streets come to life. Support booths are manned by students and volunteers. A cell phone charging station sits outside a 7-Eleven with an assortment of wires and USB cables, littered with mobile devices and batteries bearing the owners’ names with make-shift tape labels. Most of the batteries were donated by sympathetic companies and are loaned to students as needed. Another tent stocks sleeping bags that had been donated. And a friendly student offers free bottled water to passers by. The “honors” system works well. Thieves are quickly identified.

11:00 am—Streets come to life. Support booths are manned by students and volunteers. A cell phone charging station sits outside a 7-Eleven with an assortment of wires and USB cables, littered with mobile devices and batteries bearing the owners’ names with make-shift tape labels. Most of the batteries were donated by sympathetic companies and are loaned to students as needed. Another tent stocks sleeping bags that had been donated. And a friendly student offers free bottled water to passers by. The “honors” system works well. Thieves are quickly identified.

Noon—A report squawks over the radio: Student leader Chen Wei-ting (陳為廷), known by his black shirt, jaunty face, and baritone smoker’s voice, was seized by police; but the situation was not as it seemed. One of the ruling Kuomintang (KMT) political party legislators had made his hasty decision to support a bill proposed by President Ma only 30 seconds after learning about it. He had been so disrespectful of the public (80% of whom opposed the bill) to make his announcement in support of the legislation from the toilet—and was now walking outside the occupied legislature, on his way to vote in favor.

Noon—A report squawks over the radio: Student leader Chen Wei-ting (陳為廷), known by his black shirt, jaunty face, and baritone smoker’s voice, was seized by police; but the situation was not as it seemed. One of the ruling Kuomintang (KMT) political party legislators had made his hasty decision to support a bill proposed by President Ma only 30 seconds after learning about it. He had been so disrespectful of the public (80% of whom opposed the bill) to make his announcement in support of the legislation from the toilet—and was now walking outside the occupied legislature, on his way to vote in favor.

Chen happened to be outside at the time, saw the legislator’s small entourage en rout, and rushed as a one-man-flash-mob, intending to block passage. As the small scene erupted, it took five police officers to seize Chen and carry him back to safety, in the occupied legislature. The police acted to keep the peace. No one was arrested. With camera crews on the scene, the lawmaker’s secrecy had been foiled. It becomes clear why Chen, the one-man army, inspires so many.

Streets are lined with vehicles from the press, as well as conspicuously labeled vehicles from local Internet providers offering free WiFi as a clear demonstration of public outreach. Local food and beverage merchants and street vendors bring food, donating it to demonstrators. A tea shop owner brings a large bag filled with 1L cups of Asian tea for those just outside the occupied chamber.

Streets are lined with vehicles from the press, as well as conspicuously labeled vehicles from local Internet providers offering free WiFi as a clear demonstration of public outreach. Local food and beverage merchants and street vendors bring food, donating it to demonstrators. A tea shop owner brings a large bag filled with 1L cups of Asian tea for those just outside the occupied chamber.

As street gatherings reach their peak, students show their love by carrying “Free Hugs” signs, smiling at passers by. One young boy, however, was not amused and scowled almost as much as General Patton—whose rehearsed frown, arguably, won WWII.

By early afternoon, speakers have taken up their microphones. Breakout groups on the streets, led by smallgroup leaders—resembling what one might see at a mega-church—begin to discuss the problems other small, free countries have had after signing trade agreements with China. Student leaders Lin and Chen are ingenious. While they discuss public input concerning the best political strategy with lawyers inside the occupied chamber, peaceful demonstrators on the streets are not as aware of all the issues at stake. So, most of the guest speakers on the street focus on educating crowds as to the issues at hand, much like how evangelist Bill Hybels expanded his audience by preaching about Jesus with “small words” rather than the usual lofty theological lingo heard from most pulpits.

By early afternoon, speakers have taken up their microphones. Breakout groups on the streets, led by smallgroup leaders—resembling what one might see at a mega-church—begin to discuss the problems other small, free countries have had after signing trade agreements with China. Student leaders Lin and Chen are ingenious. While they discuss public input concerning the best political strategy with lawyers inside the occupied chamber, peaceful demonstrators on the streets are not as aware of all the issues at stake. So, most of the guest speakers on the street focus on educating crowds as to the issues at hand, much like how evangelist Bill Hybels expanded his audience by preaching about Jesus with “small words” rather than the usual lofty theological lingo heard from most pulpits.

A DPP aide witnessed a specific KMT legislator—notorious for his affiliation with White Wolf mafia leader Chang An-le (張安樂)—holding a private meeting with a chief policeman in Taipei. All other police had been ordered out of the room. The aide photographed the secret meeting and word quickly spread throughout Taipei. Sure enough, mafia showed up to incite violence later that day—police withdrew much like the nobles abandoned William Wallace on the battle field in Braveheart. But the peaceful protesters, armed with mobile phones, made countless videos of the incident. Peace returned quickly.

A DPP aide witnessed a specific KMT legislator—notorious for his affiliation with White Wolf mafia leader Chang An-le (張安樂)—holding a private meeting with a chief policeman in Taipei. All other police had been ordered out of the room. The aide photographed the secret meeting and word quickly spread throughout Taipei. Sure enough, mafia showed up to incite violence later that day—police withdrew much like the nobles abandoned William Wallace on the battle field in Braveheart. But the peaceful protesters, armed with mobile phones, made countless videos of the incident. Peace returned quickly.

Technically, John’s “Night Watch” never ends. Throughout the afternoon, reports trickle in slowly and steadily: A suspicious man walks the parking lot with a video camera and runs off when someone videos him in response. One of the students walks outside for a smoke break without telling security. “He can’t do that,” John expresses. “Our security needs to know who enters and exits.” The KMT planned to hold a vote at another location, intending to pass the controversial legislation in question, but the opposing party (Democratic Progressive Party—DPP) locked the doors of the alternate meeting chamber and the meeting was postponed once again.

Technically, John’s “Night Watch” never ends. Throughout the afternoon, reports trickle in slowly and steadily: A suspicious man walks the parking lot with a video camera and runs off when someone videos him in response. One of the students walks outside for a smoke break without telling security. “He can’t do that,” John expresses. “Our security needs to know who enters and exits.” The KMT planned to hold a vote at another location, intending to pass the controversial legislation in question, but the opposing party (Democratic Progressive Party—DPP) locked the doors of the alternate meeting chamber and the meeting was postponed once again.

*John is a composite. This story contains real events that have may have been combined or simplified for the sake of journalistic brevity.